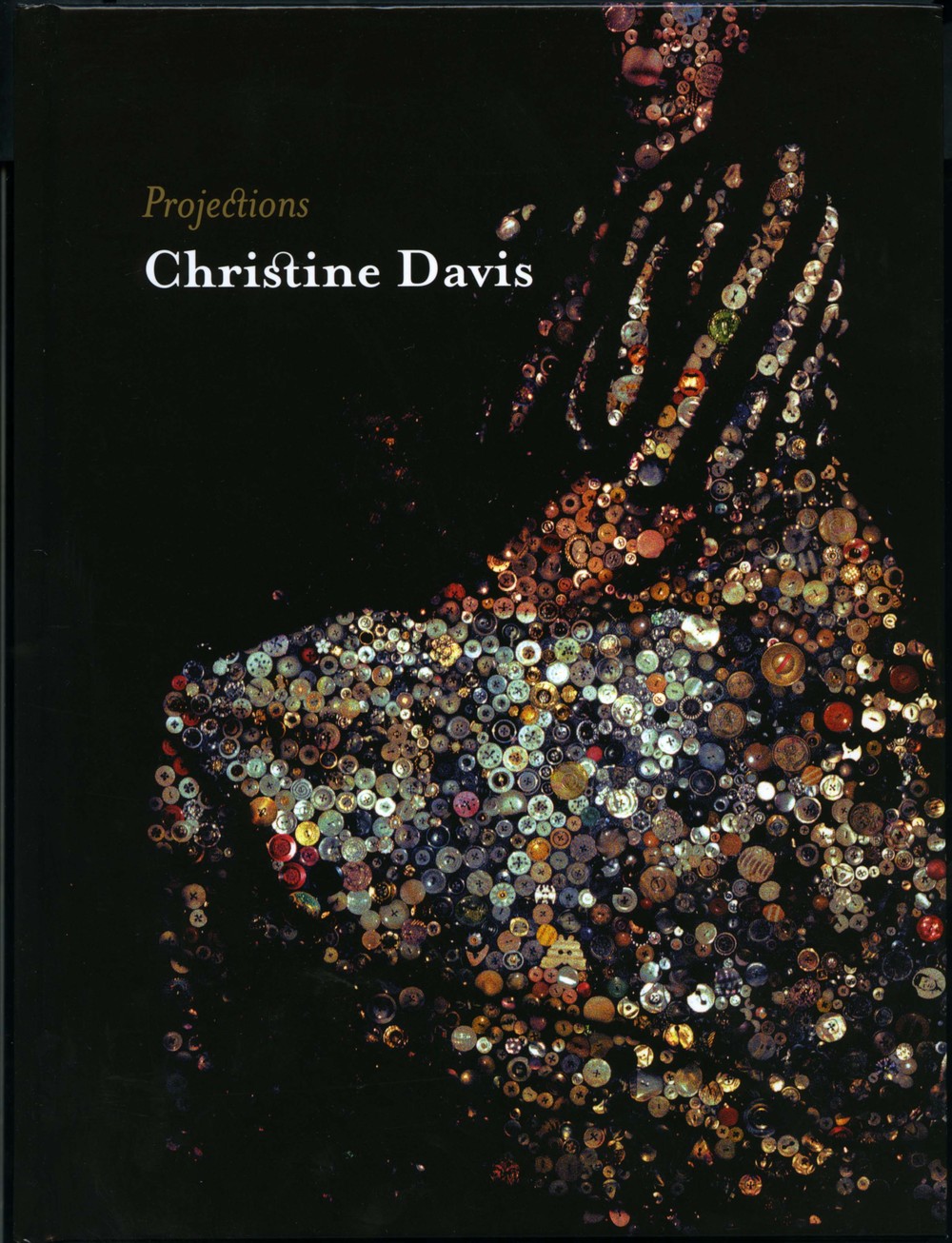

Christine Davis & the Secret Life of Screens

JANINE MARCHESSAULT

Karl Marx explained the fetish character of commodities in terms of a “secret" power:

The form of wood, for instance, is altered, by making a table out of it. Yet, for all that, the table continues to be that common. every-day thing, wood. But, so soon as it steps forth as a commodity, it is changed into something transcendent. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relations to all other commodities, it stands on its head head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, for more wonderful than “table-turning” ever was.1

The commodity form wraps the life world in a "mystical veil." It is not that the commodity is simply a fetish, but that the secret of the commodity is tied to the process of fetishization. The mysterious character of the commodity finds analogy in religion where the “products of the human mind become [...] endowed with lives of their own, able to enter into relations with men and women.”2 Thus, the product of labour makes its "appearance" through the commodity, which can be likened to an image whose origins and material production have been erased.

For Marx, long fascinated by the symbology of world religions. the political task is to return citizens to “the real world" in order to reveal the processes of material production. We see here a view of ideology as a kind of veil or screen over reality. A history of modernist aesthetics based on the committed artwork (from Georg Lukacs and Bertolt Brecht to Laura Mulvey and Hans Haacke) takes its cue from this idea of revealing the processes of production as both an ethics and a means to transform the social order by showing the truth.

Jean-Lac Nancy poses a challenging question to Marx's formula when he asks whether revealing the secret really does disclose the nature of production.3 For Nancy, this question of the demystification of the fetish opens up another space where, "behind the unveiled secret, another more convoluted secret cloaks itself.”4 What lies beneath the fetish is the very “force of desire.”5 Arguably, this is the quintessential nature of the society of the spectacle, which, as Guy Debord so forcefully asserted, cannot simply be exposed.

It is at this junction of the secret beneath the secret—what Nancy calls the “two secrets of the fetish”— that I would like to begin a discussion of the captivating and often disturbing screens that have become the hallmark of Christine Davis‘ practice. Her recent slide dissolve pieces Pluck, Tlön, and "DRINK ME" stage commodity fetishism as a "double genitive" that gives purchase to Nancy's insights. 6 In each of these works, Davis projects still photographs in dissolving sequences, calling upon the material nature of the screen and its double function as both display and mask, as transmitter and translator of the image. Davis‘ screens are themselves screened. They are framed and made into sculptural objects. They are dressed up fetishes, sometimes wearing white padded satin (Logos), feathers (Pluck), butterflies (Tlön), or silk flowers (“DRINK ME").

These screens must be read in conjunction with Davis‘ early works that investigate the relation between labour, epistemology, pain, and aesthetics—an investigation that has consistently been posed through the politics or the feminine. Her work has choreographed numerous encounters between word and flesh. For example, Le dictionnaire des inquisitors (1992), based on the infamous Repertorium Inqitisitorum (1494), is an installation made up of 308 coloured contact lenses, each engraved with one of the 308 words used to identify heresy during the Spanish Inquisition. Such deviance was written, for the most part, on the bodies of women, Jews, Moors, and indigenous peoples of the Americas. Theocratic power guided by "blinding" reason defines the installation’s specular terrain, which is more museological than performative in its rendition of an epistemology of holocaust. Again. the process of coming into being and seeing takes its shape through the dictionary etched on the lens. The contact lens itself is an invisible frame (futuristic and arcane) that filters all experience coming in or going out of the body.

Logos is Davis‘ first large screen installation with photographic projection. The white screen is twelve-by-twelve feet and hangs suspended in the middle of the darkened gallery. The screen is luxuriously upholstered in white satin. Its glamour calls to mind a movie stars boudoir were it not hanging vertically and illuminated by a film still from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s devastating indictment of the society of the spectacle, Salò or The 120 Days of Sodom (1975). Pasolini is an important influence on Davis‘ investigation of the secret or the commodity. we can see images from his films making their appearance in many her photographs. Davis shot the image off a movie screen in Paris. The subtitle “Il n'y a rien a faire" is visible on the edge of the frame. The image in the installation is itself endemic to the architectural metaphor of the Palazzo in Pasolini's film with as Italian Bauhaus style, mirrors, chandeliers, art deco artifacts, and modernist art associated with fascism.

Projected onto the padded screen are two young bodies (male and female) being masturbated. In the film, two Ducas look on from off screen. Their dialogue consists of the following, although, Logos only includes the first and last line from the exchange:

There is nothing to be done

naturally, once we are Masters of the State

In fact, the one true anarchy is that of power

Nevertheless, look!

The obscene gesticulation,

is like deaf-mutes’ language

with a code none of us,

despite unrestrained caprice,

can transgress.

There Is nothing to be done.

Salò features idealized bodies in accordance with the dictates of Sade's eighteenth-century text. For Pasolini, this capitalist economy of made-to-measure corporeal perfection calls forth consumption as excremental culture—one that feeds upon itself. Pasolini's Film resists consumption and incorporation. In its excess, it is difficult to watch and, even after so many years, its violence is abhorrent. Davis features the words “Il n'y a rien à faire", not as a pessimistic indictment but as a performance of Logos. It is a closed text that does not simply impose itself on the world but is the world. The Palazzo in both Pasolini’s and Davis' work is closed to the outside, presenting the world as screen. It is the task of art not simply to explode this screen (like the Surrealist project) but to engage with the "force of desire" that lies beneath it.

Davis' early interrogation of a petrified perfection is expanded upon in her recent screens, which have added a complex layer of temporalfly to her "framework." In Pluck, her first foray into time-based work, hundreds or black feathers line a large screen. Film frames of a female trapeze artist are ‘”plucked” from a sequence and projected in slow dissolves onto the feathers. The feathers are uniform in their appearance and compelling in their sheen. The slow dissolves disintegrate over them, creating a tactile surface. The feathered screen exemplifies the fetish. The original fetish, as Marx and Freud surmised, is tied to the sensual power or the animus as a kind of"primitive" death drive. The originary power of

the animal is appropriated by wearing its corpus. In indigenous cultures, this is generally tied to ritual and communal life based on a reciprocity between human and non-human worlds. In the capitalist incarnation, however, it is a circus of undifferentiated consumption—a spectacle where cycles of life are reduced to banal "routines." The trapeze artist dangles by her neck and spins perilously above the ground. It is precisely the control of that “split second" timing that makes the routine work. No room is left for error and the woman's body is transformed into a clock. The body in Pluck is enclosed in an atemporal space where the aleatory and the contingent—the world that is open to chance and new potentialfly—is screened out.

This theme or lost time and the animus also appears in Tlön, or How I held in my hands a vast methodical fragment of an unknown planet’s entire history, inspired by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges’ "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” (1940), a short

story that recounts the discovery of the invention of a planet by a secret society in Europe during the Enlightenment. The creation of the world was developed as a collective. Yet, Borges suggests that it must be the work of a "shadowy man of genius" since it requires “subordinating the imagination to a rigorous and systematic plan.”7 Davis‘ rendition of the story presents us with a screen made entirely out or Morpho butterflies. Like Pluck, Davis uses two synchronized machines to project photographs that dissolve into the screen. Unlike the feathers in Pluck, which are glued to the surface, the butterflies are pinned to the screen in a large collection of singular yet identical objects. The layout calls forth the natural history practice of pairing death with epistemology. Here, Davis returns to her favoured themes of the dictionary and encyclopedia, to systems of knowledge and classification that construct taxonomies rather than describe phenomenologies. And this is precisely what Borges imagines as the imagined world of the Enlightenment as he tells us how the discovery of the planetary system is attributed to “the connections of a mirror and an encyclopedia.”8 It is a system of knowledge destined to repeat and multiply.

The very space of the imagined planet that Borges‘ character uncovers is akin to the space of a screen, for on Tlön, "space is not conceived as having duration in time.’’9 Thus without time, Tlön has no intrinsic causality, every event is simply

“an association of ideas.”10 Not surprisingly, psychology is the dominant discipline on Tlön and one would not be hard-pressed to read Jacques Lacan’s famous model of the psyche as screen into Borges‘ closed system. Davis projects onto the collection of butterflies, photographs made with the earth's most advanced X-ray and gamma ray technologies. cameras capable of "capturing" images of nebulae, quasars. and supernovas. These spectacular images of the universe cannot be separated from the imagination or the technological and discursive supports of a natural history that gave them shape. Hence, the images projected onto the butterflies are themselves a methodological fragment of contemporary scientific practices. The world of distant planets is made to appear atop the butterflies. According to chaos theory, the flapping of a butterfly’s wings can affect events all the way into those distant universes. But the wings have been securely fastened and, like the bird feathers of Pluck, have long lost their affective capacity.

Yet, this is what fascinates the viewer and what makes Davis’ screens so fundamentally tactile. Tlön is a meditation on the fantastic imagination of scientific naturalism. But it is more than simply a negation of desire—in the same way that the fictions of Pasolini and Borges cannot be reduced to critique. Rather, as Nancy suggests, the "fascination and the luster of the fetish continue to adhere to its own denunciation.”11 Davis’ installation is tactile: we want to reach out and touch it, to hold it in our hand. Nancy describes this second aspect of the secret of commodity fetishism as the “desire of presence [...] the very art of art." We desire to be touched “for a single instant through their singularity, through their unique value. We reach toward them as toward the other side of death, which posits the inverted, equally unique touch of effacement in absence.”12 The fetish contains as a sign the desire to desire, a presence accumulated that gives it an enigmatic tacitly.

Let me conclude with “DRINK ME”, whose starting point is the space of self-consumption. This is without a doubt Davis’ most melancholic screen. In this installation, the sequences of projected and dissolving images, along with the very screen made of large artificial flowers, are literally devoured by the female figure in

Davis’ adaptation of Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland (1865). We see a blonde and

buxom Alice literally eating the pages from Carroll's story. At times she appears to consume the garish flowers from the screen, and at others even her own image. Davis' imagined landscape is a liquid uncanny where objects metamorphose into one another and where boundaries between objects and people disappear. Like Pasolini and Barges, Carroll, the quiet mathematician, had imagined a labyrinthinely mirrored world where commodities do speak. Of course, the female body and the screen in Davis’ installation are both objects and the

directive “drink me" is virtually pornographic.

“Wonderland" in Carroll's story presented the warped space or the newly discovered space-time of industrial modernity, which Marx describes in the famous passage, “all that is solid melts into air.''13 Yet, when Marx wrote, "Could commodities themselves speak,” he wanted them to speak through the mouth of the economist.”14 For the wonderland value of things needed to be materialized as human labour. Arguably, this materialization of labour is what "DRINK ME" accomplishes. Alice becomes the edible woman, which perhaps contributes to the melancholic character of this installation. Indeed, many of Davis‘ screens must be read in terms of an ethics that brings gender and labour together in framing commodity fetishism. Yet, her screens also allow us to contemplate the fact underlined by Nancy, that the society of tthe spectacle can never he simply exposed. There will always be a secret beneath the screen, a terrible fascination that keeps us transfixed in the dark.

1 Karl Marx, "The Fetishism of Commodities and the secret Thereof,“ Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. I, ed. Fredrich Engels, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling (New York: International Publishers, 1967), 71.

2 Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels, Selected Works I, 439, quoted in Robert Tucker, Philosophy and Myth in Karl

Marx (Cambridge. New YorkL Cambridge University Press, 1972). 206.

3 Jean-Luc Nancy, “The Two Secrets of the Fetish." Diacritics 31.4 (2001): I04.

4 Ibid,. I05.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Jorge Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Penguin Books, 1998),72.

8 Ibid., 73-74.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Nancy, “The Two Secrets of the Fetish,” 105.

12 Ibid.

13 Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (London: Penguin Books, 2004), 7.

14 Marx, "The Fetishism of Commodities and the secret Thereof,“ 74.