Introduction

HELGA PAKASAAR

Christine Davis‘ slide dissolve installations draw out the connotation of projection as Illumination and reverie, and raise questions about the nature of perception. Her image sequences are projected on textured screens suspended in complete darkness.These luminous phantasmagoria invite a process of deciphering that comes from repeated viewings of short loops. Davis exploits the attenuated pace of slide dissolve to set up mood anticipation, triggering an awareness of duration. The visual illegibility of recurring blurs, shadows, reflections, and gaps amplifies the contingencies of vision. The cinematic experience of these works thus engages perceptual states of mind and emotion call for an engaged process of apprehension.

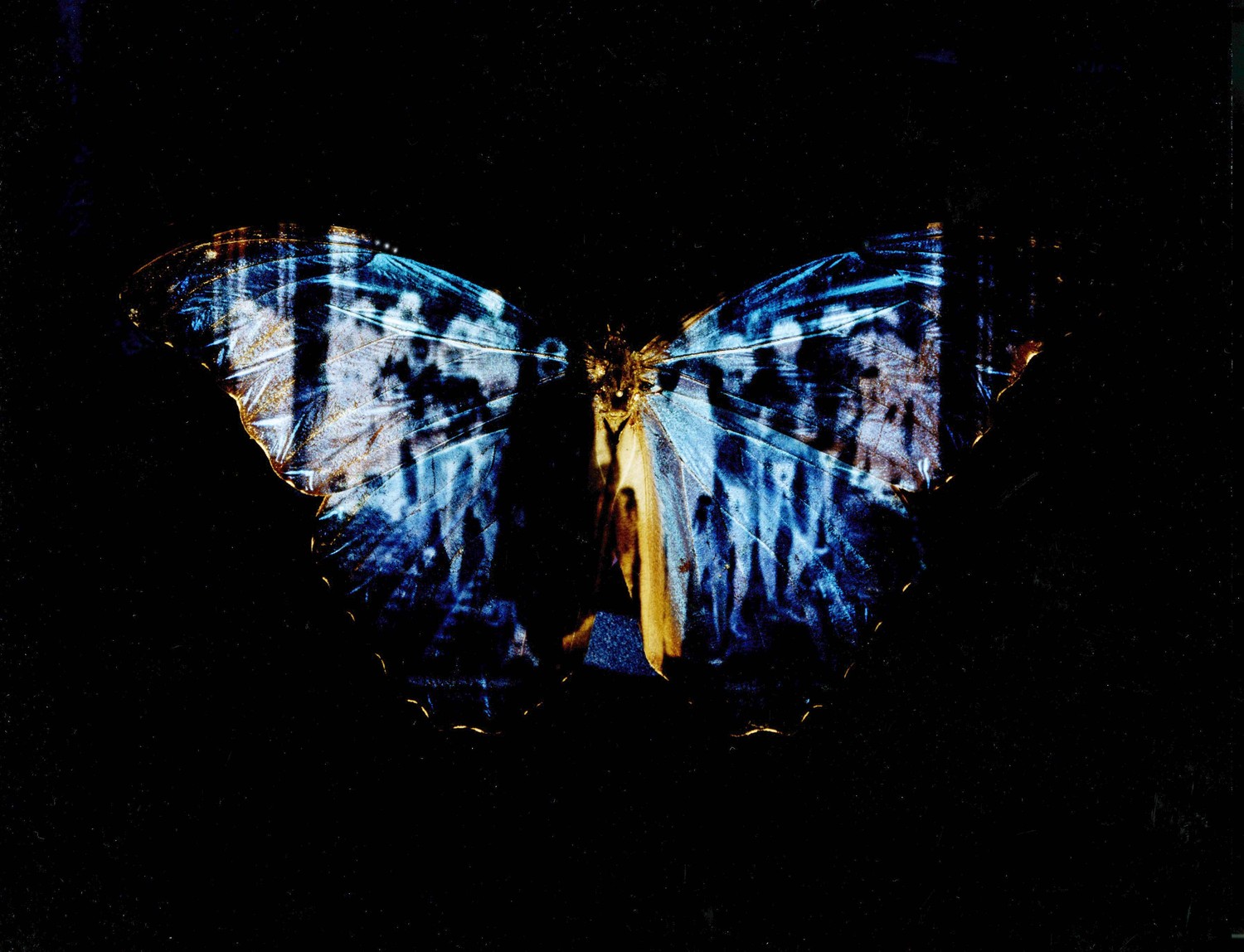

The slides are projected onto material screens, creating what the artist refers to as ‘a thickening of the image.’ Mottled image fusing figure and ground are in a perpetual state of composing and decomposing. The screens seem fluid, morphing between reflective surface and sculptural presence. At times appearing as abstract fields of colour, they are animated by an interplay of light and darkness, amplified by resonating afterimages. The material that each screen is made of (feathers, butterfly wings, buttons, plastic flowers) shifts in and out of focus. Unlike projections on symbolic objects, these surfaces are like collaborators that embellish latent meaning. This prevailing sense of transience and dissolution affirms the artist’s concern with psychic states of instability. In making obvious how display and

concealment are intertwined in the mechanics of slide dissolve, Davis sets the stage for narratives of masquerade. The psychological dynamics of seen and unseen is clearly expressed in a related series or colour photographs called ‘anagrams.’ These montages of bondage photographs from Japanese porn magazine projected onto patterned dresses seem at once monstrous and seductive. The veiled female bodies are in states of dissolution and entanglement that deflect the impulse to identify with them. The artist conceives of bodies as denaturalized sites of chaos, an idea she compellingly expresses in the spectral figures that inhabit her projection works.

Davis exaggerates such visual effects in “DRINK ME” or Alice was beginning to get very tired (2005-06), a three-minute slide dissolve sequence on a screen comprised of over-sized plastic flowers. The grid of flower heads—like a giant halftone or fractal pattern—breaks up the images. Often inspired by the literary, Davis here invokes Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). As in Carroll’s tale, the phrase ‘drink me’ is an invitation to suspend disbelief and give into an experience of ever transforming physical and mental states. In Davis’ version, Alice falls down the rabbit hole, ingests the book and becomes quite literally, the story. In this condensation of interior and exterior worlds, she becomes figure, ground and process. The bizarre female figure in a diaphanous gown, obsessively eating herself, can be seen as an expression of abjection, lunacy, or perhaps, ecstatic delirium. Yet as in Alice’s skewed world where dream and reality are so hopelessly intertwined, subjective narratives cannot hold in the delusory spaces of “DRINK ME”. At one moment she is seen as a tiny creature immersed in a field of flowers. At another, her heavily made-up face looms large, only to become a shadow absorbed into the blotches of saturated colour. Time and space seem elastic. The rhythm of these perceptual shifts—driven by the hypnotic, mechanistic pace of individual slides advancing and reinforced by the clicking and shunting noises of the apparatus filling the space—imparts a kaleidoscope of impressions.

This presence of analogue technology is intrinsic to the structure and meaning of Davis’ projections. Her works insist on a bodily relation to image, emphasized by the flickering light from the slide projections that are more akin to a blinking eye than high-speed electronic signals. Moreover, we are drawn toward the illumination to marvel; at the screen’s intricate construction and the fabrication of illusion. Quite different from film as representation and psychological space, the cinematic experience of these works is based on a material encounter—apprehension comes from a cognitive interaction with sensation. Every dissolve is palpable and light as matter has a tactile presence. Significantly, unlike the immersive spectacles of so much contemporary media art, these projections are contained visual fields in keeping with traditional pictorial conventions scaled to the human body. Indeed, their chiaroscuro effects and luck coloured surfaces, at times resembling brushstrokes, can be thought of as moving paintings, as ciphers for fascination.

Drawing out the poetics of technology, the artist brings to life the technical means of projection as play of shadow, reflection, and illumination, and more essentially, time and motion. While owing much to digital realities, and at times appearing as virtual immateriality, her works also allude to the origins of photography and film. They bring to mind, for example, phantasmagoric spectacles of light, a form of entertainment that became popular in the eighteenth century, where sides were projected from behind a translucent screen to viewers on the other side, creating an illusory play of shadowy apparitions. Davis’ projections can also be seen as spectral shows that manifest ‘ghosts of the mind’ and hallucinatory thoughts. Always elusive, they never quite settle into narrative patterns. How she reveals time and motion to be at once continuous and fragmented is not unlike chronophotography, nineteenth-century motions studies that recorded successive movement invisible to the eye, or the flickering stream of images produced by pre-cinematic optical devices. Similar to looking though a zootrope, as Davis’ dreamscapes unfold, there is a sense of being simultaneously inside and outside of illusory space. Parallels can also be drawn with the special effects of early cinema, as with Georges Méliès’ dramatizations of uncanny appearances and disappearances. A fabulist and conjuror of visual trickery herself, Davis’ fantastical cinema presents the melodramas of the psyche through a conflation of phantasmal illusion and ephemeral presence. She uses such filmic effects with considerable inventiveness.

The slide dissolve format as a form of montage allows for optimum control of temporal conditions. Typical of contemporary art that explored duration through exceedingly slow or even still footage to reveal imperceptible movement in space, Davis engages the pleasures of close observation and the sense of flux that slowness reveals. Absorption of these works is a conceptual process. Unravelling the idea of ‘persistence of vision’, her projections are a palpable reminder that cinema is a succession of still photographs. Their structure is based on the mechanics of film: Pluck and Tlön are comprised of twenty-four slide frames, or one second of film narrative, and “DRINK ME” has a twelve frame, blink of an eye, structure. Equally deliberate with sequencing, Davis photographs each frame herself, as with “DRINK ME”, or edits from existing archives. Tlön was distilled from thousands of astronomy slides and the five-minute loop of Pluck was culled from hundreds of stills shot from five minutes of found footage. These constructs reinforce the sense of fragmented time. Christine Davis’ novel form of film installation reveals the complexities and mysteries of cinematic experience.