The Electric Fairy, A Fin-de-Siècle Archeology

by OLIVER ASSELIN

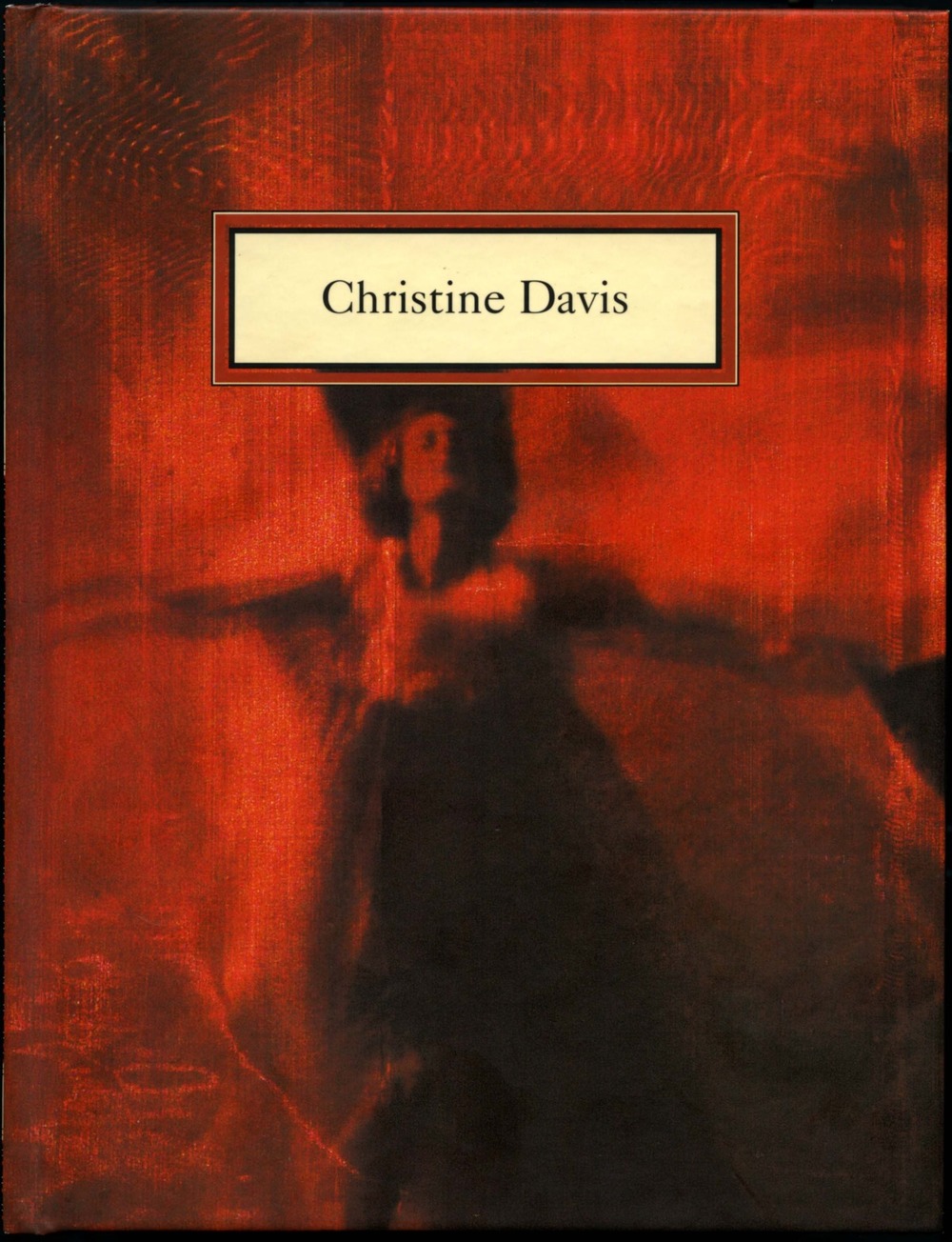

Each of the works by Christine Davis in this exhibition revisits, in its own way, a rich fabric woven from the intersecting histories of dance, film and the sciences. To do so, they employ the device of projecting selected images onto unusual support.

In appearance, Euclid/Orchid is very simple, associating a photograph and a ready-made object: an illustrated page of Euclid's Elements is projected as a negative image onto a live orchid in a pot placed on a pile of books in a corner of a room.

The work is dialectical in that it opposes a concrete object and mathematical abstraction; a complex, organic, three-dimensional form and simple, geometric, two-dimensional figures; a living thing and a dead page; an arborescent growth and logical reasoning; a limited duration and an axiomatic eternity. But by virtue of the projection, the image of the treatise acquires a temporality and a presence analogue to those of the living plant, which grows in real time. And, above all, the plant does not serve merely as a screen for the luminous image: it absorbs it, feeds on it and transforms it into chlorophyll.

Did I Love a Dream? is also simple: an old film is projected onto a screen of woven copper wire. It shows an interpretation of Loïe Fuller's famous Serpentine Dance. But since the footage is looped and reversed, the hypnotic dance is executed over and over, and backwards, defying the laws of motion and gravity.

The metal mesh screen opens up an elaborate network of metaphors: the copper wire calls to mind the circulation of electricity; crossed and crisscrossed to form a surface, it beginsto resemble the swirling fabric that the dancer tosses about; wound and unwound, it resembles the film stock that records time, image by image, folding it in on itself for later revival in a new unfolding. Here, the motif, the original support of the image and the projection screen combine in a single form: the fabric, which at once incorporates time — it is the product of spinning and weaving — and unfurls in time, when animated by movement or light. As a result, the irreversibility of time is denied. The screen is immobile, the image is looped and reversed: for a moment, time becomes reversible, cyclical and suspended.

Satellite Ballet (for Loïe Fuller) features a short video loop played on multiple groups of iPod Touches hung on the gallery’s four walls. The installation was inspired by the original choreography for L'Aprés-midi d'un faune which Nijinsky created to Debussy's music, itself inspired by Ma|larmé's poem, and transcribed using his own notation system. Each wall represents a page of the transcription, and the iPods, the position of each of the ba|let‘s characters — Faun, head nymph and other nymphs — at a precise point in the choreography. In addition, the video runs at different speeds for the different characters, as if to illustrate the dramatic contrast between them.

This video is a montage of diverse images. Most are taken from a hand-tinted film by Edison showing a Fuller imitator performing a serpentine dance. But these images are juxtaposed with others, some closely linked to Fuller— two illustrations of her costume, a printed card of a butterfly-woman — and some more distantly related - geometric diagrams from Euclid's Elements, elemental particles colliding, a particle accelerator, etc. The montage opens and closes with a few fleeting shots or Davis herself, seated at a computer in her studio, lighting a cigarette, smoking, staring below the camera at the unseen screen, perhaps watching this very video.

— ABSTRACTION —

Through montage and installation, the works assembled here associate figures and images from assorted sources belonging to various times and contexts : Fuller’s animated drapery, the orchid, the butterfly, the coloured diagrams of Euclidean geometry, the behaviour of elemental particles, etc. This association may appear arbitrary. Nonetheless, it is analogical or metaphorical: these figures are similar in terms of shape and colour, in terms of rhythm. By enveloping the body in the volumes of fabric she manipulates, Fuller transforms it into a butterfly, a flower, a rosette; by photographing and projecting it frame by frame, cinema transforms it into a luminous, mechanical form; by presenting these images in fast motion on the miniature screens of a group of iPod Touches, Davis's work ultimately reduces all this to an optical rhythm, to pure flickering.

Even so. her work is not formalist, since the network of metaphors it deploys goes beyond the strictly visual. Indeed, it emphasizes the genre of these forms. In the cultural imagination, these images are not neutral: they are polarized and associated with sexual difference in a relationship which is often simple but can be complicated at times by inversion or an infinitely differential logic. In this way, butterfly and flower, writing and paper, mathematical formula and concrete form, artist and model, technology and motif, light and screen, gaze and image, spectator and spectacle are constantly sexualized and resexualized — like the Faun and the nymphs. And Fuller’s work is an emblem of that, in which these metaphors crystallize: the female body, the organic form and the image. In the serpentine dances, and in their photographic and cinematic reprises, as well, the female body is highly fetishized: it is poised between figuration and abstraction, it is eroticized and kept at a remove, it becomes an ambivalent sign that at once affirms and denies sexual difference.

Beyond form, however, Davis's work also creates an epistemological connection between art and science, specifically around abstraction. Abstraction is a complex notion. It can be defined as a reduction, passing from the complex to the simple, or as an induction, passing from the particular to the general. And when opposed to “concrete“, it also implies an intellectualization, passing from the material to the conceptual. In science, as in philosophy, abstraction is primarily a semiotic process: it is used to produce signs, which have the advantage of being easier to manipulate than their referents. But in art, abstraction is a more purely aesthetic process, a means of producing forms, by pushing the process of abstraction so that the semiotic relationship between the sign and its referent is broken and the sign can no longer be read as a sign, but as a simple form.

Davis's work thus establishes a link between artistic abstraction and scientific abstraction, between formal abstraction and conceptual abstraction. But this comparison does not reduce scientific illustrations and visualizations to pure art forms. On the contrary, it encourages a view of pure art forms as phenomena to modelize, and of their impression on film or their notation on paper as modelizations. Fuller's animated drapery is not merely a magnificent aesthetic form that one never tires of watching, like a dancing flame. It is also a complex form that, throughout the performance, never entirely repeats itself and and constantly renews itself. This form is chaotic; it is one of those complex phenomena, like climate change and liquid turbulence, which are determined, but non-linear, and, as a result, remain largely unpredictable. As such, it prompts an epistemological reflection on the complexity of the sensible and the limits of the concept.

— ATTRACTION—

The association of these figures and these images — the animated drapery, the flower, the butterfly, the coloured circle, the path of the particles — is not simply metaphorical and epistemological. It is also, of course, historical. These figures and these images have contiguous and causal relationships. They appeared at the same time, at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century; they paved the way for it or followed from it. And the figure of Loïe Fuller is at the crux of it.

Long neglected in the canonical history of dance, Loïe Fuller (I862-I928) has become the subject of renewed interest and is rightly considered one of the three great American pioneers of modern dance, together with Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan. In I892 in New York, she débuted the Serpentine Dance which would earn her worldwide fame. Soon after, she took this number to the Folices-Bergére, where she created a sensation, particularly among “moderns” like Toulouse-Lautrec, who drew her, and Mallarmé, who wrote about her in glowing terms. She went on to triumph at the 1900 Universal Exposition, and for all this she was dubbed “Fée Lumière" (fairy of light).

Fuller’s practice probably derived from the cancan and the skirt dance, which were popularized in France, England and the United States at dance halls and in cabarets, music halls and variety theatres. But Fuller took these dances to new heights by vastly expanding the surface of the ‘‘skirt'‘ and projecting coloured light forms onto it. From then on, she demonstrated inexhaustible ingenuity: colourfully pattered robes, projectors with gelatine filters and painted glass slides, mobile projectors, an immense veil attached to a headdress and animated by means of two long wands, stage hung in black, to isolate the dancing form, or surrounded by mirrors, to fragment and multiply the form to infinity, phosphorescent salts applied on a black gown, ultraviolet rays, shadows projected on a screen, rays of light rising out of the floor, glass pedestal on which the performer appeared to he suspended in air, reflecting tinfoil costumes, etc.

The "skirt" hid the performer's body to transform it into a form at one organic, evoking both butterfly and flower, and, especially, abstract, freed from the ground and the laws of gravity, and then into a projection surface, which the luminous coloured shapes ultimately fragmented, kaleidoscope-like, into a pure visual form. This aspect of the performance moved Mallarmé to describe Fuller as “a phantom“ that produces a “spiritual effect,“ a truly “dazzling spectacle."(1)

It is not surprising that the nascent art of motion pictures looked to skirt and serpentine dances which, because they turned the body into an animated image, were already cinematic. In fact, these dances appear in many films from that era — some, possibly, with Fuller herself. (2) This spontaneous encounter between Loïe Fuller and the cinema confirms — albeit needlessly — Gaudreault and Gunning's argument that early cinema was primarily conceived not as a narrative but as at attraction, as the display of a phenomenon, or a spectacular image or device.3This is why the cinema quickly seized on Loïe Fuller and Loïe Fuller blossomed on the screen.

— NON EUCLIDEAN GEOMETRIES —

These figures and images crossed paths in the late nineteenth century not only in the realm of attractions but also in the field of science. Fuller, as we know, was already drawing partial inspiration from the sciences of the day. She counted scientists among her friends and very early on installed her own laboratory to conduct optical and chemical experiments, and develop new lighting effects. At the same time, science was taking a keen interest in the human body in motion, and using print and photographic images in numerous research projects, including the chronophotographic study or movement. All of these practices came together here, in the cinema, beyond the opposition of science and attraction.

However, these figures chiefly call to mind modern physics, an emerging disclpline that was questioning Euclidean geometry through serious speculations on the so-called non-Euclidean geometries and their three, four and even n dimensions, which would lead straight to the theory of relativity. From that point on, time was no longer absolute but relative to the observer, and space was no longer Euclidean— homogeneous and isotropic — but well and truly curved. This was the intellectual context that saw the development of projective geometry and topology, which deal not with figures but with their spatial distortions and their continuous transformations, according to complex operations.

In this context, Fuller‘s dance takes on another meaning. The drapery is a complex surface, like the Möbius strip or Klein bottle, whose front, back, inside and outside are indistinguishable: it is a two-dimensional surface, curved in the third dimension and animated in the fourth dimension (time), on which other flat figures are projected and distorted. Fuller's flower can thus be seen as emblematic of a scientific paradigm shift.

— THE MODERN EPISTEME —

Davis’s project explores an elaborate network of formal, epistemological and historical relations that entwine around the figure of Loïe Fuller. From this perspective, her work is archeological, in the Foucauldian sense of the term. Firstly, it is historiographic: it takes the past for its subject and borrows the methodology of historical research; it works with historical materials, documents and monuments. Secondly, it looks not only at official history, but also at micro-history — the margins of undersides of history, the neglected, seemingly insignificant details. Thirdly, it deals less with objects, agents and events as such than with the discourses and practices to which they belong. And lastly, it does not examine a single discourse or a single practice but, rather, envisages a whole configuration of discourses, practices, technologies and institutions.

Like Foucauldian archaeology, such work assumes that, because they are contemporary, these discourses and these practices belong to the same epistemological and historical order, to the same episteme — a questionable hypothesis, of course, since history may not possess the continuity we suppose, either in its diachrony or in its synchrony. Be that as it may, this art, like history, contributes to the archaeology of modernity, but with its own means and aims. As opposed to history, which is still essentially textual and transparent, art pays special attention to the very materials, media and technologies that it employs, to their physical, aesthetic, social and historical properties. Also contrary to history, which aims to objectively describe and explain bygone times, art looks upon the past — in its formal, figurative, narrative and even allegorical dimensions — as a reservoir of beauties, moral teachings and, especially, meanings. For all these reasons, art is at times better able than historiographic discourse to plumb the profound meaning of history — and of current events. We see this in the exemplary work of Christine Davis.

Translated by MarciaCouëlle

1. Stéphane Mallarmé, in a passage titled “Autre étude de danse : Les fonds dans Ie ballet" from the piece “Crayonné au théâtre," first published in the collection Divagations in 1897. Reissued as Igitur; Divagations, Un coup de dés (Paris, Gallimard, 1976), p. 198-201. Quoted in English from Mallarmé in Prose, 2001.

2. In 1894, Edison captured the fleeting movements of the Fuller imitator Annabelle Whitford Moore in her version of the dance in a magnificent hand-tinted film. In 1895, the Lumière brothers filmed Loïe Fuller herself performing the Serpentine Dance. In 1897, Edison made another film, which is titled Crissie Sheridan but appears to feature Loïe Fuller again. Shortly after that, Pathé produced several films on the same theme (1900,1901, 1905). Fuller is also credited with the performance, direction and hand-tinting of the Gaumont production Fire Dance (1906). Also for Gaumont, she later made the feature-length Le Lys de la vie (1921), based on a script by her friend Queen Marie of Romania.

3. See André Gaudreault and Tom Gunning, "Le cinéma des premiers tempos: un défi a l'histoire du film ?," in Historie du cinéma. Nouvelles approches, ed. Jacques Aumont, André Gaudreault and Michel Marie (Paris: Publication de la Sorbonne, 1989), p. 49-63. See also Tom Gunning, "The Cinema of Attractions: Early Cinema, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde," in Early Cinema: Space Frame Narrative, Thomas Elsaesser, ed. (London, British Film Institute, 1990), p. 56-62.